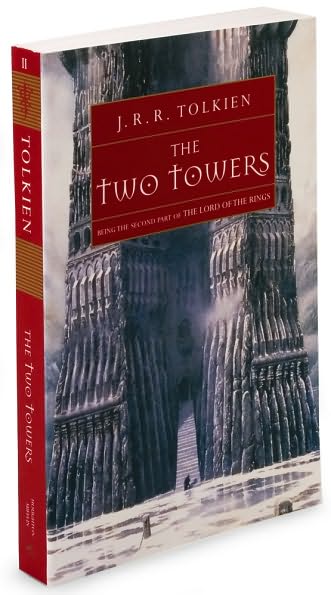

So in my down time and for relaxation, I've taken to reading The Lord of the Rings. In January, in Rome, I read all of the first in the series: The Fellowship of the Ring, and have begun the second: The Two Towers. The books are thrilling.

Amidst all of the exciting yet treacherous adventure and the high speech harkening to the majesty of great times, Tolkien takes the opportunity to address various issues. In his first book, I noticed he very early on addressed the question of the death penalty and its use in societies which have rather good ways of removing criminals from society. Whether Tolkien is doing this purposefully and specifically intending to address these issues (or if his own authoring just brought him to the point of addressing the issue and--being a good Catholic--he decided to show how he thinks these great men he is intending to depict would address the issues thoughtfully and virtuously) I do not know.

Amidst all of the exciting yet treacherous adventure and the high speech harkening to the majesty of great times, Tolkien takes the opportunity to address various issues. In his first book, I noticed he very early on addressed the question of the death penalty and its use in societies which have rather good ways of removing criminals from society. Whether Tolkien is doing this purposefully and specifically intending to address these issues (or if his own authoring just brought him to the point of addressing the issue and--being a good Catholic--he decided to show how he thinks these great men he is intending to depict would address the issues thoughtfully and virtuously) I do not know.

Well, as I read, he just did it again, but this time more generically in regard to morality. In this passage it comes to the question of culture and relativism. I'll let Tolkien do the talking (pp. 427-428):

‘Then what do you think has become of them?’ [asked Éomer.]

‘I do not know.' [said Aragorn.] 'They may have been slain and burned among the Orcs; but that you will say cannot be, and I do not fear it. I can only think that they were carried off into the forest before the battle, even before you encircled your foes, maybe. Can you swear that none escaped your net in such a way?’

‘I would swear that no Orc escaped after we sighted them,’ said Éomer. ‘We reached the forest-eaves before them, and if after that any living thing broke through our ring, then it was no Orc and had some elvish power.’

‘Our friends were attired even as we are,’ said Aragorn; ‘and you passed us by under the full light of day.’

‘I had forgotten that,’ said Éomer. ‘It is hard to be sure of anything among so many marvels. The world is all grown strange. Elf and Dwarf in company walk in our daily fields; and folk speak with the Lady of the Wood and yet live; and the Sword comes back to war that was broken in the long ages ere the fathers of our fathers rode into the Mark! How shall a man judge what to do in such times?’

‘As he ever has judged,’ said Aragorn. ‘Good and ill have not changed since yesteryear; nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves and another among Men. It is a man’s part to discern them, as much in the Golden Wood as in his own house.’

Tolkien then addresses the conflicts we all experience. We know of laws, rules and regulations, but occasionally (perhaps rarely!) we find ourselves in a situation in which two real, actual goods are in conflict. He continues by showing the need for sincere discernment and prudential judgment in regard to these less graves matters and laws when such conflicts arise between goods. Again, Tolkien:

‘True indeed,’ said Éomer. ‘But I do not doubt you, nor the deed which my heart would do. Yet I am not free to do all as I would. It is against our law to let strangers wander at will in our land, until the king himself shall give them leave, and more strict is the command in these days of peril. I have begged you to come back willingly with me, and you will not. Loth am I to begin a battle of one hundred against three.’

‘I do not think your law was made for such a chance,’ said Aragorn. ‘Nor indeed am I a stranger; for I have been in this land before, more than once, and ridden with the host of the Rohirrim, though under other name and in other guise. You I have not seen before, for you are young, but I have spoken with Éomund your father, and with Théoden son of Thengel. Never in former days would any high lord of this land have constrained a man to abandon such a quest as mine. My duty at least is clear, to go on. Come now, son of Éomund, the choice must be made at last. Aid us, or at the worst let us go free. Or seek to carry out your law. If you do so there will be fewer to return to your war or to your king.’

Éomer was silent for a moment, then he spoke. ‘We both have need of haste,’ he said. ‘My company chafes to be away, and every hour lessens your hope. This is my choice. You may go; and what is more, I will lend you horses. This only I ask: when your quest is achieved, or is proved vain, return with the horses over the Entwade to Meduseld, the high house in Edoras where Théoden now sits. Thus you shall prove to him that I have not misjudged. In this I place myself, and maybe my very life, in the keeping of your good faith. Do not fail.’

‘I will not,’ said Aragorn.

I must say, I am a personal fan of the movies which came out within the last decade. I thought and think they are excellent. Luckily, though, I had not read the books before watching them for the first half-dozen times or so. I still appreciate the movies since that is how I came into this whole endeavor. Nevertheless, books can do much more than movies can for plots and story development and so I have to say that the books have been far better.

If you have not taken the time to read these books, I really do commend them unto you. I have not been disappointed; I have been quite pleased; and I'm not even to the best part yet!